Solar Orbiter gets world-first views of the Sun’s poles

Thanks to its newly tilted orbit around the Sun, the ESA-led Solar Orbiter spacecraft is the first to image the Sun’s poles from outside the ecliptic plane. This unique viewing angle will change our understanding of the Sun’s magnetic field, the solar cycle and the workings of space weather.

Any image you have ever seen of the Sun was taken from around the Sun’s equator. This is because Earth, the other planets, and all other operational spacecraft orbit the Sun in the ecliptic plane. By tilting its orbit out of this plane, Solar Orbiter reveals the Sun from a whole new angle. On 23 March 2025, Solar Orbiter was viewing for the first time the Sun from an angle of 17° below the solar equator, enough to directly see the Sun’s south pole. Over the coming years, the spacecraft will tilt its orbit even further, so the best views are yet to come.

"Today we reveal humankind’s first-ever views of the Sun’s pole," says Prof. Carole Mundell, ESA's Director of Science. "The Sun is our nearest star, giver of life and potential disruptor of modern space and ground power systems, so it is imperative that we understand how it works and learn to predict its behaviour. These new unique views from our Solar Orbiter mission are the beginning of a new era of solar science."

Solar Orbiter's world-first views of the Sun's south pole

The collage above shows the Sun’s south pole as recorded on 16–17 March 2025, when Solar Orbiter was viewing the Sun from an angle of 15° below the solar equator. This was the mission’s first high-angle observation campaign, a few days before reaching its current maximum viewing angle of 17°.

The images shown above were taken by three of Solar Orbiter’s scientific instruments: the Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI), the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI), and the Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment (SPICE) instrument.

"We didn’t know what exactly to expect from these first observations – the Sun’s poles are literally terra incognita," says Prof. Sami Solanki, who leads the PHI instrument team from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany.

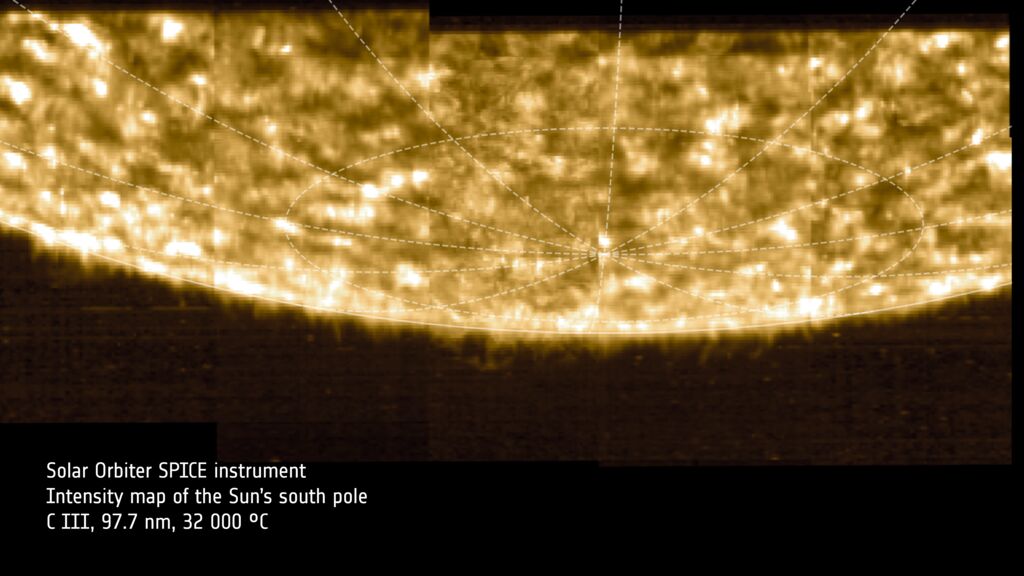

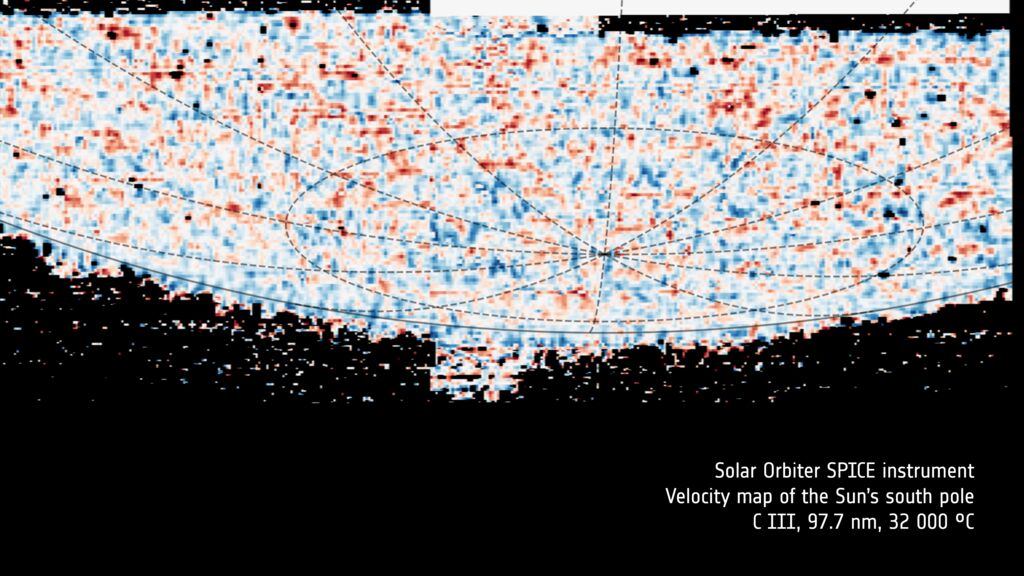

One ‘first’ of these Solar Orbiter observations comes from the SPICE instrument, of which IAS is Principal Investigator. Being an imaging spectrograph, SPICE measures the light (spectral lines) sent out by specific chemical elements – among which hydrogen, carbon, oxygen, neon and magnesium – at known temperatures. For the last five years, SPICE has used this to reveal what happens in different layers above the Sun’s surface. Now for the first time, the SPICE team has also managed to get velocity maps, which reveal how solar material moves within the thin layer called the 'transition region’, where the Sun's temperature rapidly increases from 10 000 °C to hundreds of thousands of degrees.

Crucially, Doppler measurements can reveal how particles are flung out from the Sun in the form of solar wind. Uncovering how the Sun produces solar wind is one of Solar Orbiter’s key scientific goals. "Doppler measurements of solar wind setting off from the Sun by current and past space missions have been hampered by the grazing view of the solar poles. Measurements from high latitudes, now possible with Solar Orbiter, will be a revolution in solar physics," says SPICE team leader, Frédéric Auchère from IAS.

SPICE sees the Sun's south pole, in a C³⁺ spectroscopic line emitted in the transition region: intensity and Doppler shift.

These are just the first observations made by Solar Orbiter from its newly inclined orbit, and much of this first set of data still awaits further analysis. The complete dataset of Solar Orbiter's first full ‘pole-to-pole' flight past the Sun is expected to arrive on Earth by October 2025. All ten of Solar Orbiter’s scientific instruments will collect unprecedented data in the years to come.

"This is just the first step of Solar Orbiter's 'stairway to heaven': in the coming years, the spacecraft will climb further out of the ecliptic plane for ever better views of the Sun's polar regions. These data will transform our understanding of the Sun’s magnetic field, the solar wind, and solar activity," notes Daniel Müller, ESA’s Solar Orbiter project scientist.

Link: ESA press release.

Contact at IAS: Frédéric Auchère